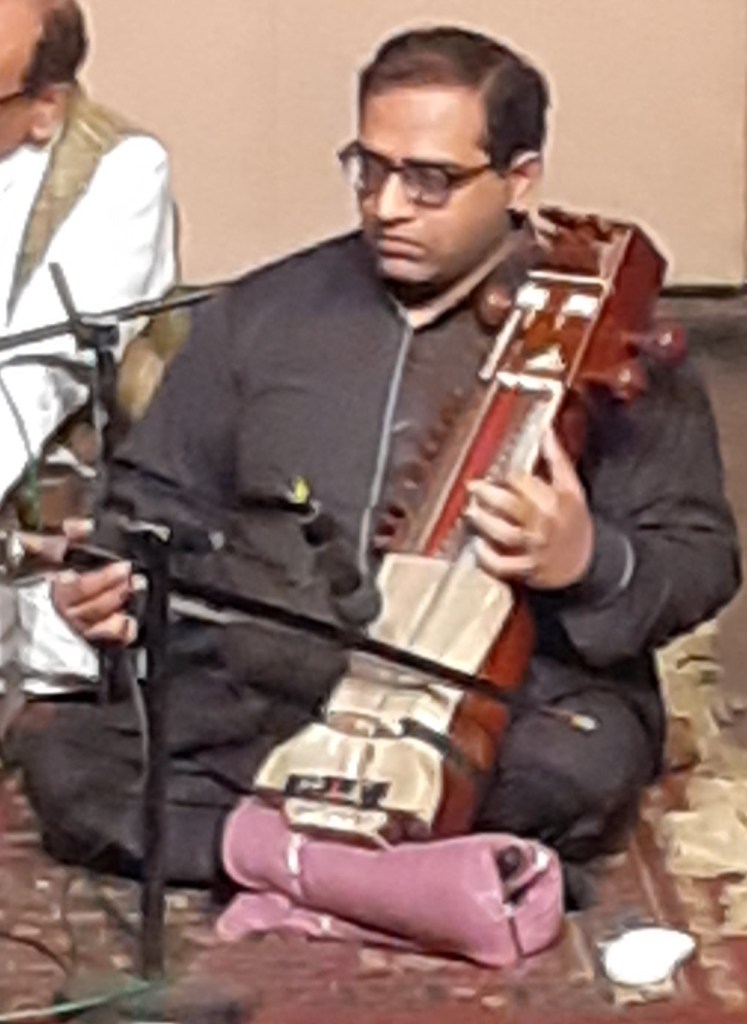

The Instrument with a Hundred Voices

No-one is quite sure what the sarangi’s name is meant to mean. Some argue that it comes from the Persian for ‘three strings’, while others claim that it means ‘a hundred colours’, a reference to its incredible musical range. Whatever it means, one cannot deny that that very name is now synonymous with Pakistani classical music, despite the instrument’s starting out as a simple folk instrument, very much like the humble ektara.

The sarangi first achieved fame in the Mughal era, when classical music was flourishing due to the patronage of the Mughals. Even though no-one is not quite sure of when exactly this happened, we do know that the sarangi soon became a staple of classical music performances, filling in the very role the violin filled in Western classical music.

However, the sarangi’s popularity began to fade soon after the arrival of the harmonium. This new arrival was both easier to learn and play, leading to the sarangi’s being neglected in its favour, even though the harmonium cannot render the ‘meend’ (slide between notes) which is so essential to classical music, unlike the sarangi. Although we at Save the Sitar recognize the harmonium as an incredibly versatile and convenient instrument, we firmly believe that it should not take the sarangi’s rightful place. It is urgently required that the sarangi be preserved in Pakistan so that generations to come may enjoy and appreciate it.

Picture courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Save the Sitar is a website dedicated to promoting and preserving Pakistan’s classical music. Join our growing community to help further our cause!

Follow Save the Sitar!

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.